IS AID HURTING AFRICA?

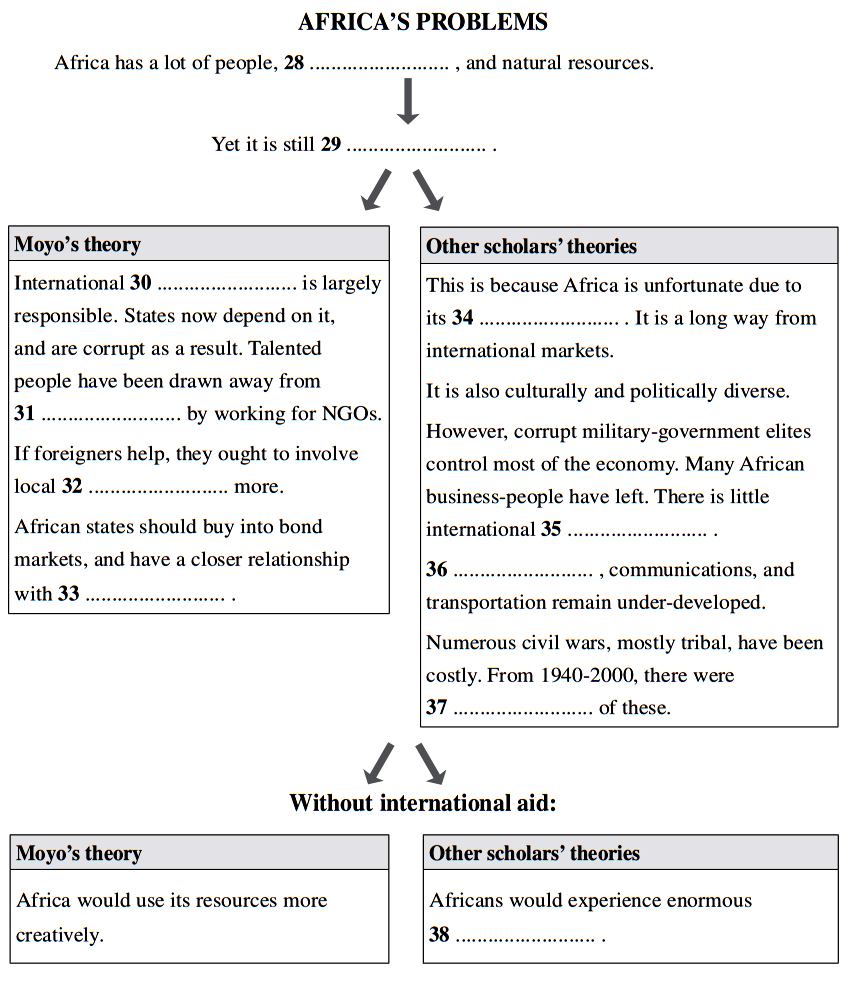

Despite its population of more than one billion and its rich land and natural resources, the continent of Africa remains poor. The combined economies of its 54 states equal that of one European country: the Netherlands.

It is difficult to speak of Africa as a unit as its states differ from each other in culture, climate, size, and political system. Since mid-20th-century independence, many African states have pursued different economic policies. Yet, none of them has overcome poverty. Why might this be?

One theory says Africa is unlucky. Sparsely populated with diverse language and culture, it contains numerous landlocked countries, and it is far from international markets. Dambisa Moyo, a Zambian-born economist, has another theory. In her 2009 book, Dead Aid, she proposes that international aid is largely to blame for African poverty because it has encouraged dependence and corruption, and has diverted talented people from the business. One of her statistics is that from 1970-98, when aid to Africa was highest, poverty rose from eleven to 66%. If aid were cut, she believes Africans would utilise their resources more creatively.

When a state lacks the capacity to care for its people, international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), like Oxfam or the Red Cross, assume this role. While NGOs distribute food or medical supplies, Moyo argues they reduce the ability of the state to provide. Furthermore, during this process, those in government and the military siphon off aid goods and money themselves. Transparency International, an organisation that surveys corruption, rates the majority of African states poorly.

Moyo provides another example. Maybe a Hollywood star donates American-made mosquito nets. Certainly, this benefits malaria-prone areas, but it also draws business away from local African traders who supply nets. More consultation is needed between do-gooder foreigners and local communities.

Moyo also suggests African nations increase their wealth by investment in bonds, or by increased co-operation with China.

The presidents of Rwanda and Senegal are strong supporters of Moyo, but critics say her theories are simplistic. The international aid community is not responsible for geography, nor has it anything to do with the military takeover, corruption, or legislation that hampers trade. Africans have had half a century of self-government and economic control, yet, as the population of the continent doubled, its GDP has risen only 60%. In the same period, Malaysia and Vietnam threw off colonialism and surged ahead economically by investing in education, health, and infrastructure; by lowering taxes on international trade; and, by being fortunate to be surrounded by other successful nations.

The economist Paul Collier has speculated that if aid were cut, African governments would not find alternative sources of income, nor would they reduce corruption. Another economist, Jeffrey Sachs, has calculated that twice the amount of aid currently given is needed to prevent suffering on a grand scale.

In Dead Aid, Moyo presents her case through a fictitious country called ‘Dongo’, but nowhere does she provide examples of real aid organisations causing actual problems. Her approach may be entertaining, but it is hardly academic.

Other scholars point out that Africa is dominated by tribal societies with military-government elites. Joining the army, rather than doing business, was the easiest route to personal wealth and power. Unsurprisingly, military takeovers have occurred in almost every African country. In the 1960s and 70s, European colonials were replaced by African ‘colonials’ – African generals and their families. Meantime, the very small, educated bourgeoisie has moved abroad. All over Africa, strongmen leaders have ruled for a long time, or one unstable military regime has succeeded another. As a result, business, separate from the military government is rare, and international investment limited.

Post-secondary education rates are low in Africa. Communications and transportation remain basic although mobile phones are having an impact. The distances farmers must travel to market are vast due to poor roads. High cross-border taxes and long bureaucratic delays are par for the course. African rural populations exceed those elsewhere in the world. Without a decent infrastructure or an educated urbanised workforce, a business cannot prosper. Recent World Bank statistics show that in southern Africa, the number of companies using the internet for business is 20% as opposed to 40% in South America or 80% in the US. There are 37 days each year without water whereas there is less than one day in Europe. The average cost of sending one container to the US is $7600, but only $3900 from East Asia or the Pacific. All these problems are the result of poor state planning.

Great ethnic and linguistic diversity within African countries has led to tribal favouritism. Governments are often controlled by one tribe or allied tribes; civil war is usually tribal. It is estimated each civil war costs a country roughly $64 billion. Southern Africa had 34 such conflicts from 1940-2000 while South Asia, the next-affected region, had only 24 in the same period. To this day, a number of bloody conflicts continue.

Other opponents of Moyo add that her focus on market investment and more business with China is shortsighted. The 2008 financial crisis meant that countries with market investments lost money. Secondly, China’s real intentions in Africa are unknown, but everyone can see China is buying up African farmland and securing cheap oil supplies.

All over Africa, there are untapped resources, but distance, diversity, and low population density contribute to poverty. Where there is no TV, infrequent electricity, and bad roads, there still seems to be money for automatic weapons just the right size for 12-year-old boys to use. Blaming the West for assisting with aid fails to address the issues of continuous conflict, ineffective government, and little infrastructure. Nor does it prevent terrible suffering.

Has aid caused problems for Africa, or is Africa’s strife of its own making or due to geography? Whatever you think, Dambisa Moyo’s book has generated lively discussion, which is fruitful for Africa.

Questions 1-11

Complete the chart on the following page.

Choose ONE WORD OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

(image Q28-38)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11 1

Questions 12-13

Choose TWO letters: A-E.

Which of the statements does the writer of Passage support?

A Moyo is right that international aid is causing Africa’s problems.

B Moyo has ignored the role of geography in Africa.

C Convincing evidence is lacking in Moyo’s theory.

D Most political leaders in Africa agree with Moyo’s analysis.

E Useful discussion about Africa has resulted from Moyo’s book.

---End of the Test---

Please Submit to view your score, solution and explanations.