Solution for: The Plan to Bring an Asteroid to Earth

Answer Table

Exam Review

The Plan to Bring an Asteroid to Earth

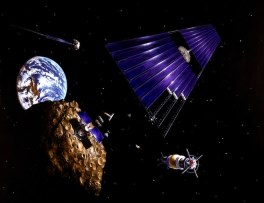

Scientists and engineers met last week at Caltech to discuss the possibility of capturing an asteroid and placing it in orbit near Earth to use as a base for manned space missions further into the solar system.

PASADENA, Calif. — Send a robot into space. Grab an asteroid. Bring it back to Earth orbit.

This may sound like a crazy plan, but it was discussed quite seriously last week by a group of scientists and engineers at the California Institute of Technology. The four-day workshop was dedicated to investigating the feasibility and requirements of capturing a near-Earth asteroid, bringing it closer to our planet and using it as a base for future manned spaceflight missions.

This is not something the scientists are imagining could be done some day off in the future. This is possible with the technology we have today and could be accomplished within a decade.

A robotic probe could anchor to an asteroid made mostly of nickel-iron with simple magnets or grab a rocky asteroid with a harpoon or specialized claws (see video below) and then push the asteroid using solar-electric propulsion. For asteroids too big for a robot to handle, a large spacecraft could fly near the object to act as a gravity tractor that deflects the asteroid’s trajectory, sending it toward Earth.

“Once you get over the initial reaction — ‘You want to do what?!’ — it actually starts to seem like a reasonable idea,” said engineer John Brophy from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who helped organize the workshop.

In fact, many of these ideas have been on the drawing board for years as part of NASA’s planetary defense program against large space-based objects that might threaten Earth. And there’s no shortage of potential targets. NASA estimates there are 19,500 asteroids at least 330 feet wide — large enough to detect with telescopes — within 28 million miles of Earth.

Though rearranging the heavens may seem an excessive undertaking, the mission has its merits. The Obama administration already plans to send astronauts to a near-Earth asteroid, a mission that would coop them up in a tiny capsule for three to six months, and involve all the risks of a long deep-space voyage. Instead, robots could shoulder some of that burden by bringing an asteroid close enough for astronauts to get there in just a month.

Considering the resources available in any asteroid, private industry might be interested in getting involved. One possible mission would be to simply execute the first part of the plan — pushing the asteroid to near-Earth orbit — and then convene a commercial competition inviting anyone who wants to develop the capabilities to reach and mine the object.

Though the undertaking might be scientifically exciting, this wouldn’t be the primary motivation. An asteroid would provide great insight into the solar system’s formation, it’s not enough to justify the expense of bringing one to Earth. Any interesting science can be done much cheaper with an unmanned robotic spacecraft, said chemist Joseph A Nuth from NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center.

“Ultimately, we would be developing this target in order to help move out into the solar system,” Brophy said.

Though they did not reach a consensus on all the details, the group will reconvene in January to hammer out further specifications and potentially get the interest of NASA.

In the end, many agreed that bringing an asteroid back to Earth could create an interesting destination for repeated manned missions and that the undertaking would help build up experience for future jaunts into space.

Other Tests

-

Total questions: 13

- 6- TRUE-FALSE-NOT GIVEN

- 7- Summary, form completion

-

-

Total questions: 14

- 9- TRUE-FALSE-NOT GIVEN

- 5- Summary, form completion

-

Total questions: 13

- 5- TRUE-FALSE-NOT GIVEN

- 4- Sentence Completion

- 4- Summary, form completion

-

Total questions: 13

- 4- YES-NO-NOT GIVEN

- 6- Matching Information

- 3- Plan, map, diagram labelling

-

Total questions: 14

- 5- Matching Headings

- 4- Matching Information

- 5- Summary, form completion